The Face of Freedom is a piece that was written to draw attention to the real-life stories behind the slavery statistics regularly seen in the news.

Read morePowers Of Truth: Badiucao

The following article is a collaboration with Disruption Network Lab , in the context of its 24th Conference “POWERS OF TRUTH” which took place between 1-3 October 2021. More information is found at the end of the article.

Badiucao in front of one of his works, “Carrie Lam,” a portrait of Hong Kong’s chief executive, at Santa Giulia Museum in Brescia, Italy. Image Credit: Alessandro Grassani for The New York Times .

On 26 October 2021, I had the pleasure to interview Badiucao, the world renowned artist and dissident from China, currently living in exile in Australia. After failing to arrange a call earlier in the month, I rushed to contact him upon learning of his upcoming exhibition in Brescia (Italy), titled China is (not) near: Badiucao, which has been attacked by the Chinese Embassy’s cultural office and threatened to be censored.

As an Italian myself, I was curious to understand what prompted Badiucao to choose Brescia as its preferred venue for his exhibition. He explained it was an old friend’s suggestion – art curator Elettra Stamboulis - who initially pitched the idea of Brescia as cultural centre, in light of the internationally acclaimed festival the city hosts, named Peace, which traditionally invites human rights supporter artists. Notably, in its 2019 edition, the festival featured Kurdish dissident artists exiled from Turkey, who have endured political imprisonment there. As such, Brescia seemed to be the ideal location to continue the tradition of supporting human rights defenders and promoting their art.

Badiucao’s exhibition was due to happen in October 2020, but was postponed until 2021 due to COVID- related restrictions and delays, which hit particularly hard in the Northern areas of Italy, including Brescia. Despite the circumstances, it presented a unique and special opportunity for Badi, who struggled with having his own space and gallery to exhibit his art. His native China was a no-go from the outset, because of national security concerns; Australia was equally unsuitable, he explained, because of the tangible influence China retains on Australian people and culture, which extends to cultural institutions and its curators. The latter appear to be rather scared of the Chinese influence, as they rely heavily on the Chinese market for funding and subsistence.

For more than three years, the only opportunity for Badiucao to exhibit his art in Australia was at the Street Art Festival in 2019. He shared his frustration with me by stressing how the Festival is not an institution, nor a museum, let alone a commercial gallery, which significantly curbs his market penetration and impact.

Before Brescia, Badiucao has had chances to showcase his pieces in the United States: he held a residency programme in San Francisco, and subsequently an outdoor exhibition at the 2021 edition of the Olso Freedom Fund , held in Miami and organised by the Human Rights Foundation .

While in the States, Badiucao collaborated with Turkish NBA player and outspoken human rights advocate Enes Kanter – now known as Enes Freedom – to produce “protest shoes“ displaying “Anti-Beijing” slogans, criticising the Communist regime’s abuses and violent dissent suppression, with particular reference to “Beijing’s state-sponsored oppression against the Uyghurs ,” forced labour, and the Tibetan occupation.

But the Italian exhibition is pivotal for another reason: it constitutes Badiucao’s first major solo art exhibition in his entire career, and truly provides him with the opportunity to showcase all the work that did not get a chance to be displayed in Hong Kong in 2018. This represents Badiucao’s core art portfolio, portraying his entire career’s evolution, from its inception, till present date. What this portfolio conveys is an ever-expanding definition of art, which exudes from Badiucao’s varied art practice, which spans from political illustrations, to oil paintings, installations, performance art, and general gallery practice.

© Badiucao, retrieved from the Time Magazine online.

The Exhibition: La Cina non è Vicina (China is not near)

As for its content, the exhibition, on display at the Santa Giulia Museum until 13 February 2022, will feature a series of portraits, immortalising the image of China’s famous Covid-19 early whistleblower, Doctor Li Wenliang. Badiucao explains how this concept can be easily introduced in the exhibition, by virtue of the similarities that the Northern city of Brescia has faced at the outset of the pandemic, when the emergency status was at its peak: Brescia was heavily damaged by the pandemic’s initial aftermath, and its people suffered quietly, similarly to the turmoil endured by the people in Wuhan.

Doctor Wenliang’s story, which is officially censored by the Chinese government, is the story of how a pandemic could have been avoided, or, at the very least, curbed from the start. It unravels uncomfortable questions about Chinese values, Badiucao told me. He believes that his work will expose China’s internal governmental issues, alongside its seemingly tilted moral compass. He also is optimist that his work will provide a reasonable portrayal of China’s missteps, to hold its government accountable, as opposed to unsubstantiated, biased, and offensive racist conspiracy theories.

Next to the portrait series, Badiucao curated a display of Wuhan residents’ diaries during the lockdown period - a selection of 100-day diaries – where the spectator is confronted with just how brutal and severe the situation truly was: the diaries serve as a medium to fully expose China’s lies on how sophisticated and efficient the Chinese contingencies plans and decontamination practices were. They provide an excellent record of history that can be used to defeat harmful Chinese propaganda in the future, as they embody the thinking and experiences of ordinary citizens. They constitute a free and safe environment for the Chinese people, who are not much different from the people in Brescia: both, and all, pursuing their fundamental human rights and dignity.

The question arises on whether the diaries can be classed as an artwork. Badiucao explained how he obtained the diaries via social media, giving a voice to the people who cannot express themselves as they are being forcibly silenced by their governments. In this way, the diaries represent an expanded form of art, which transcends the material creation of the particular artist, encapsulating a higher message of freedom.

The pretence of human rights universalism

Mid-call, I decide to ask a purposely provocative question, addressing the criticism directed at the pretence of “universalism” of human rights and the way they are understood. I hint at the argument advanced by the CCCP in stating that the Chinese nation and its people simply hold an entirely different value-system from that of the West, placing collectivism and sacrifice ahead of individual rights. Badi immediately proceeded to dismantle this argument systematically, by stating that the CCCP has the least authority to discuss the realities and values of the Chinese people’s culture: if we look at history, he says, we will quickly understand that the CCCP is responsible for destroying Chinese culture from its core, repeatedly - the real root of Chinese culture has been annihilated, he sadly asserts. Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution provides a very crude example of said destruction, which effectively amounted to a cultural purge , and constituted the most brutal example of instrumentalised nationalism used to promote the regime’s propaganda.

© Badiucao, retrieved from The Diplomat online.

Interestingly, Badiucao brings into the discourse the philosophy of Confucius, which notably celebrates individualism, as opposed to the collectivist cultural claims mentioned above. However, Badiucao is cautious in praising Confucius unconditionally, and briefly explains to me how his philosophy was manipulated by Chinese emperors throughout history as a practice to advance merciless authoritarianism and personal power.

Famously, the Ching dynasty, under which China was united for the first time by emperor Qui Shi Huang, imposed its factual and cultural rule much like Nazi Germany did, burning all books other than those embodying the philosophy of Confucius. That is how the Sage became so popular, its precepts spilling over Western culture so prominently. However, this eclipsing popularity does not expunge the existence of other equally important philosophical sources in Chinese history, which addressed the ideological foundations of freedom and democracy. However, those got destroyed by rulers consumed by power, such as emperors and autocrats. To conclude, Badiucao goes back to my original comment, about collectivism and sacrifice, and states that the logic of that claim has been dangerously oversimplified in history, and its current study is plagued by a problematic methodology. He also adds that the true nature of the collectivist ideology comes from the Soviet Union, not from the cultural roots of the Chinese people. We move on and I ask him to tell me about his hopes and fears for the future.

Wrapping it up

He starts by reflecting on his journey so far: just like myself, Badiucao initially studied law, in an attempt to fulfil the trope of the “model good citizen” - and student - of China. But that quickly changed, when he started to come to terms with the increasingly claustrophobic sentiment of being cornered into a fixed, Monday-to-Friday office job; that is when he started his art practice. Those were politically dark times, with an ever-increasing risk of censorship, which prompted him to search for an alternative future. He found refuge in Australia, where he studied Education and taught in schools, before embarking on its full-time art career.

Future Looks Bright

When looking at the future, he envisions the realisation of a museum-level gallery for his art, to propel his visibility: in this way, he will be able to concentrate his efforts on fine arts – expanding his practice to a proper gallery space.

He reflects on what cartooning means to him, and says it is a way of seeing the world; a visual journal to crystallise specific moments in time; historic contingencies and systemic issues in our reality. But the cartoon is not the final destination: it represents a flowing practice that never arrives, but constantly evolves.

Badiucao anticipates an increase in his use of multi-media art, particularly in the digital art space. The soar of NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) adopting blockchain technology presents an advantageous opportunity from multiple angles: the anonymous and neutral nature of online space holds great potential not only for economic profit, but to build a lasting and secure platform for political art – a territory which Badi is eager to explore.

The publishing industry also features on the list of new expansive ventures, where Badi wishes to issue comics and graphic novels.

Lastly, Badi speaks about the value of his art, which depends heavily on people’s understanding of China and the Chinese discourse: he wishes to contribute to a useful and important record of history and society by creating his art.

ABOUT DISRUPTION NETWORK LAB

Disruption Network Lab is an ongoing platform of events and research focused on the intersection of politics, technology, and society. The organisation has since 2014 developed participatory and interdisciplinary international events at the intersection of human rights and technology with the objective of strengthening freedom of speech, and exposing the misconduct and wrongdoing of the powerful. The goal of the Disruption Network Lab is to present and generate new possible routes of social and political action within the framework of digital culture and information technology, shedding light on interventions that provoke political and social change. It offers a platform of discussion to share ideas and visions for a free Internet and a modern democracy, with the aim to strengthen human rights values and freedom of speech.

POWERS OF TRUTH

The conference POWERS OF TRUTH, curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli (Director, Disruption Network Lab) and Magnus Ag (Journalist, Human Rights Advocate, Founder of Bridge Figures), brought together artists, journalists, activists, and tech experts inside and outside China to better navigate and understand dominant narratives around China we are exposed to from Beijing to Washington and Brussels, from Silicon Valley to Shenzhen. The conference POWERS OF TRUTH focused on the importance of understanding the current Chinese context analysing three main streams: technological impact, artistic experimentation and human rights protection in China and beyond.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that politics, economies, and technical infrastructures defy borders. What is developed in the Eastern part of the world influences on a large scale what is happening in Europe, as well as in the South and the West. China is expanding its influence in the world economy and in the technological sectors, growing very rapidly and lifting millions out of poverty, while defining new geopolitical alliances. As U.S. strategic engagements with China shift from one Administration to the next, the European Union is forced to develop its own strategies for how long-term regional and global stability is ensured and democratic values upheld. How can we look at the Chinese context advocating for human rights and democracy beyond propaganda and mainstream political narratives?

Badiucao’s exhibition, La Cina non è Vicina (China is not close) will be on display at the Santa Giulia Museum in Brescia (Italy) until the 13 February 2022.

Photo of Badiucao in 2020 for a Sydney Morning Herald profile, retrieved from Artists at Risk Connection

Badiucao (Chinese: 巴丢草; born c. 1986) is a Chinese political cartoonist, artist and rights activist based in Australia. He is regarded as one of China’s most prolific and well-known political cartoonists. He adopted his pen-name to protect his identity. Badiucao utilizes satire and pop culture references to convey his message. He often manipulates archetypal images from Communist Party propaganda to make subversive political statements. His work has been used or published by Amnesty International, Freedom House, BBC, CNN and China Digital Times; and has been exhibited around the world. He asserts that the government authorities in China are very concerned that their suppression of human rights activism is attracting attention from international media. He is now being pursued by China and remains in exile.

Twitter: @badiucao

The System's Grim

My least favourite thing about the law is how inaccessible it is for those who have not studied it academically. Since graduating in 2019, I have struggled with the idea of going into formal legal practice, meaning forming part and parcel of this exclusionary machine; a cog in a broken system. As I searched for alternative opportunities to help victims of this justice system, I discovered the 'Miscarriages of Justice Organisation' ('MOJO'): this brilliant charity, founded by Paddy Hill, gives legal help to those wrongfully convicted in Scotland; provides UK-wide aftercare support; and educates and campaigns on the issues surrounding miscarriages of justice.

My time spent with MOJO has heavily influenced my art practice. At university, miscarriages of justice are rarely mentioned. It is a matter that society generally overlooks unless it comes in the ‘glamourous package’ of a 10-part Netflix documentary.

If a person is found guilty of a crime in a court of law, that verdict is deemed to be the definitive ‘truth’ – both in law, and in fact; ‘justice’ is thus served, and the case is ultimately closed. Innocent people can be wrongfully convicted, but they are considered an anomaly because the system is deemed to work ‘right’. Right?

Wrong. Official statistics, retrieved from a Freedom of Information Freedom of Information (FOI) response by the Justiciary Office in May 2021, state otherwise: in Scotland, between the years 2016-2020, there were 1070 conviction appeals intimated; of those, only 288 made it past the sift stage - just over a quarter -, and were heard by the Appeal Court (26.9%). The Appeal Court only allowed 67 of these conviction appeals to proceed - therefore only formally recognising 6.2% of these first instance verdicts as an actual miscarriage of justice.

Moreover, these statistics only refer to the number of appeals intimated (that is, made formally known). There are other reasons for the official numbers of miscarriages of justice’s victims not being entered into the system. One such reason includes a plea-bargain scenario: that is, where the accused has struck a deal with the Crown Prosecution Service to accept a lesser charge, in return for a lighter sentence. The reasons for an innocent person to choose this course of action can be manifold: among others, there is the relief provided by the certainty of the outcome, as opposed to the risk of taking a case to court; pressure from external forces; the specific line of advice given by the legal team, which, albeit formally unable to dictate the defendant’s conduct, may indicate that a plea-bargain is the best option in the client’s circumstance.

From the moment a conviction of a person claiming innocence is upheld, a second, unofficial trial begins. Only around a quarter of those who appeal their case, will have a chance to be heard in the Court of Appeal. This will take years. In total, only 6.2% of all conviction appeals are successful on the grounds of a miscarriage of justice. Once a wrongly convicted person wins their appeal, one would like to believe there is appropriate compensation for years spent locked up. Right?

Wrong. There is only one way that the wrongly convicted can receive compensation in Scotland: that is on the grounds of 'fresh evidence'. It does not matter, procedurally speaking, whether the accused has been set up by the police, or had poor representation. The years of life spent behind bars won’t be compensated.

But what sort of payment could those who do fit the criteria for a successful compensation claim expect to receive? Between 2016-2020, among the 67 miscarriages of justice formally recognised by the Court, a sum of £376,987.00 was paid out to individuals wrongly convicted in Scotland. This includes interim payments and payments made to individuals who were found to be eligible before 1 January 2016. This information was retrieved by a Freedom of Information (FOI) Response by the Justiciary Office dated 10 August 2021.

We do know that not all of these cases are eligible for compensation, due to the ‘fresh evidence’ stipulation mentioned earlier. However, we can pretend, for argument's sake, that all 67 individuals received an equal share of the total sum paid out: that would be just over 5 and a half thousand pounds (£5,500), for years of their life wrongfully imprisoned. Justice served?

The system is similar but not identical to that in England. If you are fortunate enough to live on English soil, the state is legally entitled to take a percentage of your unlikely compensation to cover your ‘bed and board’ costs whilst wrongly imprisoned.

I was stunned. I had studied law for four years and had no idea about any of this. If I had no clue as a law graduate with first-class honours, what chance would someone with no formal legal education have to ever come across this information?

I aspire to be a Robin Hood-like figure of the legal art world. Taking morsels of legal knowledge from lawyers and dispensing it to the general public in the digestible – and accessible - form of art.

The project: “The System’s Grim”.

This project is still in its early stages, but will eventually become an all-encompassing exploration of the Scots criminal justice system – specifically, its human impact on victims affected by a miscarriage of justice.

The first concept includes painted portraits that will be distorted and warped. The purpose is to introduce viewers to the faces of those innocent people behind the drawings. Each portrait will be accompanied by more work explaining the story of injustice behind each individual. One concept will focus on depicting time lost. COVID has taught all of us that a year can feel like a lifetime, with many people comparing life under lockdown to prison-like conditions. Now, let us imagine 25 years of lockdown. Then, 25 years of actual prison. Finally, 25 years of being in actual prison, for something that you did not do.

25 years is the length of time served behind bars by one innocent person involved in the project: Robert Brown.

Aged 19, Brown was wrongfully convicted for the murder of Annie Walsh in 1977. The interviewing police officers framed Brown by falsifying evidence including testimony. He is one of the minority groups who succeeded in securing compensation for the manifest miscarriage of justice he suffered.

However, because he was convicted in England, he was ordered to pay £100,000 pounds to the State out of his total compensation, for his bed and board. None of the police officers involved has been charged ever since.

Released in 2002, the Court of Appeal took a mere thirteen (13) minutes to decide Brown was innocent.

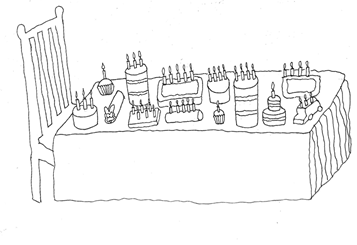

The 25 years he lost behind bars will be represented as an installation of 25 rotting cakes. They represent the 25 ‘lost’ birthdays due to his wrongful conviction. The untouched cake symbolises the good - just out of the wrongfully convicted’s reach. The dripping candles, yet to be blown, show a waiting without purpose. The mould depicts the rotten nature of the system.

A final concept in its early stages is an adult’s storybook. This will illustrate more general information about the CJS (Criminal Justice System), depicting the shocking statistics regarding miscarriages of justice. This will group complex pieces of information into an easy visual format.

Art is how I plan to bridge the gap between the legal system and the lay public it is supposed to serve.

Edward Hopper said: “If I could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint.”

Relegating the stories of miscarriage of justice victims to the mere written medium portrays a diluted narrative of the victims’ experiences. Allowing their voices to be embodied through art is something that will provide more impact, because, at times, things need to be seen and felt too, on top of being read.

Anne Flynn’s work aims to bridge the gap between the criminal justice system and the lay public it is supposed to serve. Graduating in 2019 with a first-class law degree from the University of Strathclyde, Flynn aims to make the law more accessible by removing the need to navigate its linguistic minefield. She has developed a practice of expressive interpretation of case law, statutes and statistics, allowing an examination of the criminal justice system through painting and installation. Flynn is currently studying Fine Art in Glasgow, where her work aims to employ her knowledge of the law to shock and inform her audience.

Annex

LIST OF IMAGES (Copyright © Anne Flynn 2021, with an explicit right of publication and indefinite use given to Human Rights Pulse)

Image 1) Warped sketch of Robert Brown.

Image 2) Sketch of cake installation.

Image 3) Pen-drawing of cake installation.

Image 4) Mould study – materials include: cotton wool and pastels.

Image 5) Mouldy cake painting.

Image 6) Baked Bean illustration. See Docherty v HMA (2016) HCJAC49

Cartooning For Change

THE BEGINNING

I have always loved drawing. As a child, my favourite pastime was doodling and reading cartoon magazines such as MAD, Ujang and Gila-Gila (they are famous Malaysian magazines). Growing up, I did not have the confidence to take up art more seriously or to share my work with anyone. 10 years ago, I finally realised my passion and believed in my talent as a cartoonist and comic artist.

Figure 1 My cartoon on the Arab Spring drawn in 2011

It was the year of the Arab spring. I was in the United Kingdom, pursuing my post-graduate study at the University of York. It was the same year that I also came to terms with my mental health problem. To channel my frustrations and beat my loneliness, I started to draw cartoon sketches of my experience dealing with my mental health issue. Gradually, some of my classmates started to notice my talent. I recalled my first Arab-spring inspired cartoon. It was raw and amateur, drawn with an ink pen on an A4 paper that was later scanned and edited with my haggard iPhone. My cartoon strokes were hasty and careless- marking the work of a very eager but inexperienced artist. Despite the limitations, I found the ability to express my views through my cartoons very liberating. From cartoons on Arab Spring shared in the Middle East students’ Facebook page, my catalogue of work grew. Living in the UK exposed me further to the art and comic scene. I started to immerse myself in the work of Joe Sacco , and Art Spiegelman . These new discoveries continued to strengthen my conviction in the power of visual storytelling. In 2013, I moved to Switzerland for a new job and thus began my journey to find my voice as a comic artist and cartoonist.

WHY DO I DRAW CARTOONS AND COMICS?

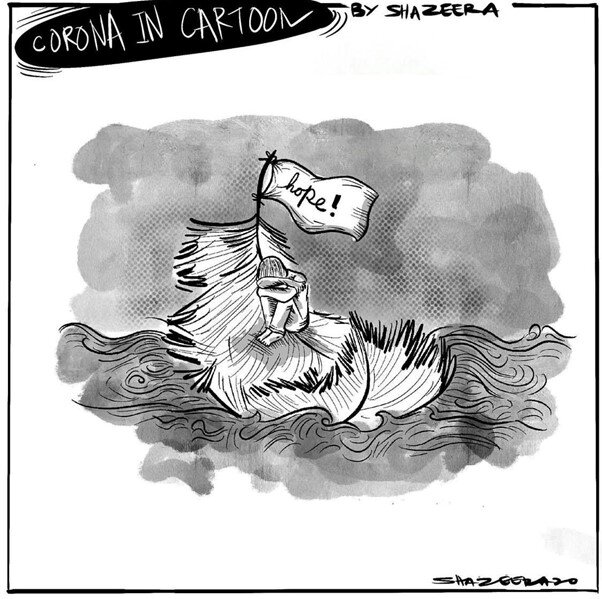

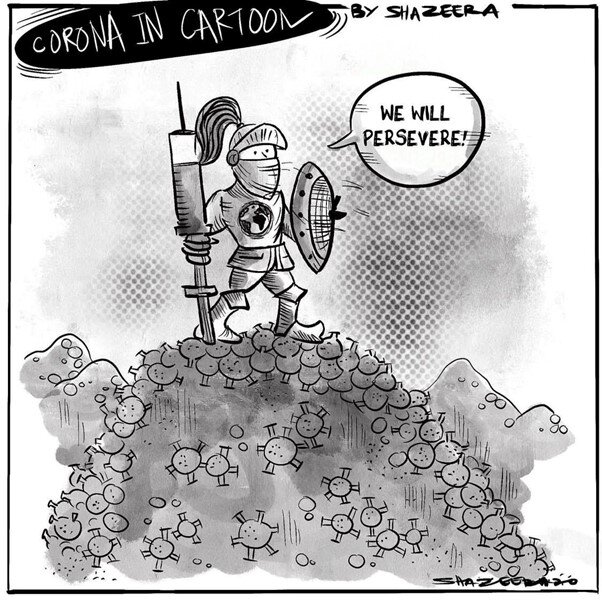

Drawing my views about human rights came naturally to me. As Marjane Satrapi , a comic artist, succinctly put it: “Drawing is the first language of the human being before writing. It is a transcription of how the human being sees reality, not reality itself”. Drawing cartoons or comics is my way of digesting and making sense of my reality and worldview, particularly during the COVD-19 pandemic. We all were seeking ways and outlets to process the situation and for me, it was by translating my views and feelings into cartoons or comics.

Human rights issues are often complex, but they are presented in the media or official documents in ways that are either unrelatable or sensationalised for the public. Such an approach risks dehumanising the victims in those cases. On the contrary, I find comics and cartoons as persuasive and palatable forms of communication that could build public understanding and empathy about human rights. Furthermore, the power of image transcends language, social barriers and textual or verbal complexities. Remember the Sunday comic strips - Snoopy or Garfield?

During the pandemic, I drew cartoons depicting some of the glaring human rights problems faced by communities around the world. While I drew inspiration from different contexts, themes such as hope, fear, grief, and loneliness are universal. A cartoon I drew on the sense of isolation suffered by an old man, was based on the tragic deaths in a South Korean long term care facility when the pandemic began. In the news report, the fear of “living alone”, “losing contact with the outside world” or “dying of loneliness” were recurring themes.

The elderly, persons with mental health issues, forced migrants, and children in conflict zones are some examples of vulnerable people that continue to be invisible and forgotten, especially during the pandemic. My cartoons aim to bring to light the plight of the voiceless and the universal themes associated with their issues. Artists, in general, may choose and have chosen to refrain from injecting empathy in their work. As a human rights advocate, I struggle to remain neutral or apathetic with my comics and cartoons. I concur with what Joao de Brito, a Portuguese-American impressionist, once said: “empathy is what is channelled by many artists to express what needs to be seen or heard from the public when the world is in confusion”.

CARTOONING AND HUMAN RIGHTS ADVOCACY

Cartoons and comics are a powerful medium to expose injustices and idiosyncrasies that are often overlooked or avoided by mainstream media. My work as a human rights advocate enabled me to collaborate with other human rights defenders, torture survivors, and governments on a regular basis. When I shared my cartoons in talks or workshops, the discussions that followed were enriched with perspectives that were beyond the issues or problems depicted in the cartoons. People were engaged and excited to use the cartoons as an entry point to explore bigger subjects such as impunity, sexism, or discrimination.

As I draw more cartoons and comics, the lessons I learned along the way help me establish some key steps in my creative process. They include the importance of building the right messages for the right audience, respecting the stories, data, and contexts, especially when it involves persons living in vulnerable situations, and injecting elements of hope and empathy in the artwork. Furthermore, it is also important that my artworks celebrate human resilience, the power of the people, and their potential to drive change. I want to ensure that the cartoons and comics I draw not only highlight the problems, but offer positive visual narratives that can cultivate hope and inspire dialogue about human rights.

I will continue to mobilise human rights advocacy and discourse in my work, one cartoon at a time.

Shazeera is a Malaysian born artist who is currently a Senior Adviser on Research and Innovation with the Association for Prevention of Torture, a Swiss-based organisation. A lawyer by training, she has produced and published her comics and cartoons for the International Commission of Jurists Thailand, and Asia Legal Resource Centre’s Journal on Torture. She also had her work exhibited as part of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s 2016 Campaign on Countering Violent Extremism and the International Fumetto Comics Festival in Luzern 2019. In 2019, she was part of Malaysia’s ´Cartoonist Against Torture´ coalition launched by the National Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (SUHAKAM) and one of her comics was featured as the cover for the Swiss Foreign Department of Foreign Affairs Action Plan Against Torture. This year, two of her works were exhibited in the first regional human rights cartoon exhibition in ASEAN. Her work has been translated into French, Malay, Spanish, Thai, Turkish and Ukrainian.

Illustration: COVID-19 In India

The plate the candle is sitting on is the shape of the Ashoka Chakra, the wheel of time, with each of the 24 spokes reflecting the hours of the day and virtues which are at the centre of the Indian flag.

Doctors and nurses who sought to commemorate the lives lost to Covid-19 lit candles in their honour. It is also a common practice in Indian households to keep a candle burning or an oil lamp lit for 10-14 days after the loss of a loved one.

Poem: The Law of Humanity By Benson Egwuonwu

“...the law of humanity,

which is anterior to all positive laws,

obliges us to afford them relief,

to save them from starving...”

so said an English court in 1803

in a judgment ruling

that poor foreigners should not go hungry,

before the genocide and national flight

of the 20th century,

there was, in this land,

a law of humanity.

before the signatures were borne

for international treaties,

to help those travellers

who we know today as refugees

whose destination is the safety they seek

there was once, in this land,

a law of humanity.

but beware the myth of a nation

riding the phoenix road to national pride

it leaves an ashen contempt

for stories from a different side

if self-determination and liberty

are ideals worthy of our species,

humanity allocated by flag stripes

should give us pause for sobriety

for in the measure of justice

there is a simmering disconnect

can a court offer confidence

without the chance of access

refugees are thwarted at borders

and dumped into detention

Parliament argues

while souls float in the Mediterranean.

so it goes

bombs and boats

machine guns and stowaways

missiles

and the economy class of a plane

midnight escape from rape

knife in the spine

privilege averts its gaze

red top headline

diplomatic communique

rebels in retreat

bribery at the gates

papers are exchanged

exhale on terra firma

a new garden called home

now surrounded by racist fervour

the survivor stands alone.

all bound by common consequence

man-made violence

man-made opportunity

man-made silence

man-made impunity.

but

the law of humanity

the cause of philosophical quarrels

which flows through the ages

and shakes the scales of our morals

anterior to all positive laws

etched on stone and parchment

your conscience knew the path

before you drew the quill to mark it

obliges us to afford them relief

with bread and shelter indeed

the only conditions relevant

are that you're human and in need

to save them from starving

for life is the sacred harvest

no child should become a corpse

because our dignity has departed.

there was, in this land,

a law of humanity

there must be a law

fit to break the boomerang of history

a law of humanity

beyond books and civility

a law that speaks

to our most intimate moments of sanity

a law of humanity

that dwells deeper than our family trees

a law that rips the fiction

out of our hypocrisies

the law of humanity

entrenched against the oppressor's creed

the law of humanity

that stands with refugees.

Notes

1. R v Inhabitants of Eastbourne (1803) 102 ER 769, per Lord Ellenborough C.J.

Benson Egwuonwu is a lawyer and poet based in London, United Kingdom. He has worked on international human rights interventions with The Law Society of England and Wales.

Poem: The Pain By Katie Bedrossian

The Pain:

The pain runs deep and cuts like a knife

Will Armenians ever see recognition in this life?

Our hearts are heavy, and the genocide denial weighs us down

Now and then we need to fix our crowns

And remember that we are strong people who will be heard one day

Every year on 24th April, Armenians fight for recognition and have something to say

In a world where our voices are silenced by people who do not seem to care

It is Armenian stories that we will continue to share

Tomorrow is another day; we will wipe away our tears

Words cannot explain how difficult it has been these last 106 years

To my fellow Armenians, we are beautiful and strong

The history of our surviving ancestors shapes us to carry on

As Armenians, we have each other to lean on,

We will never forget where we have come from.

Katie Bedrossian is a recent Sociology graduate from Coventry University. She is passionate about her Armenian heritage and is eager to act as a leader for underrepresented communities. Her specific interests include tackling injustice on gender, race, culture, and immigration. Katie is eager to pursue a career in social change where she believes her ideas can have a positive impact on society.

Poem: Daunte’s Day by Tofunmi Odugbemi

Day by day we lose our light

Asking ourselves if there is a day where we must not fight

Uncertainly moving in a cloak of fear

No one stopping to truly hear

Today is another day, a Black man is gone

Every day is another day, a Black woman is gone

Why can they not see our humanity

Righteously applauding small moments of justice after intense brutality

I can no longer stand to watch us suffer in vain

Grappling with the communal fall out of our pain

Holding out for a sign of lasting change

Tentatively waiting for another day.

Read more about this topic here.

Tofunmi Odugbemi is a challenger and disrupter of spaces. She applies her developed sense of justice, ingenuity, and leadership in areas where academia intersects with the legal world. Womanism, Black feminism, anti-ableist, anti-racist, anti-establishment, abolitionist, anti-capitalist, and queer movements inform her work.