My least favourite thing about the law is how inaccessible it is for those who have not studied it academically. Since graduating in 2019, I have struggled with the idea of going into formal legal practice, meaning forming part and parcel of this exclusionary machine; a cog in a broken system. As I searched for alternative opportunities to help victims of this justice system, I discovered the 'Miscarriages of Justice Organisation' ('MOJO'): this brilliant charity, founded by Paddy Hill, gives legal help to those wrongfully convicted in Scotland; provides UK-wide aftercare support; and educates and campaigns on the issues surrounding miscarriages of justice.

My time spent with MOJO has heavily influenced my art practice. At university, miscarriages of justice are rarely mentioned. It is a matter that society generally overlooks unless it comes in the ‘glamourous package’ of a 10-part Netflix documentary.

If a person is found guilty of a crime in a court of law, that verdict is deemed to be the definitive ‘truth’ – both in law, and in fact; ‘justice’ is thus served, and the case is ultimately closed. Innocent people can be wrongfully convicted, but they are considered an anomaly because the system is deemed to work ‘right’. Right?

Wrong. Official statistics, retrieved from a Freedom of Information Freedom of Information (FOI) response by the Justiciary Office in May 2021, state otherwise: in Scotland, between the years 2016-2020, there were 1070 conviction appeals intimated; of those, only 288 made it past the sift stage - just over a quarter -, and were heard by the Appeal Court (26.9%). The Appeal Court only allowed 67 of these conviction appeals to proceed - therefore only formally recognising 6.2% of these first instance verdicts as an actual miscarriage of justice.

Moreover, these statistics only refer to the number of appeals intimated (that is, made formally known). There are other reasons for the official numbers of miscarriages of justice’s victims not being entered into the system. One such reason includes a plea-bargain scenario: that is, where the accused has struck a deal with the Crown Prosecution Service to accept a lesser charge, in return for a lighter sentence. The reasons for an innocent person to choose this course of action can be manifold: among others, there is the relief provided by the certainty of the outcome, as opposed to the risk of taking a case to court; pressure from external forces; the specific line of advice given by the legal team, which, albeit formally unable to dictate the defendant’s conduct, may indicate that a plea-bargain is the best option in the client’s circumstance.

From the moment a conviction of a person claiming innocence is upheld, a second, unofficial trial begins. Only around a quarter of those who appeal their case, will have a chance to be heard in the Court of Appeal. This will take years. In total, only 6.2% of all conviction appeals are successful on the grounds of a miscarriage of justice. Once a wrongly convicted person wins their appeal, one would like to believe there is appropriate compensation for years spent locked up. Right?

Wrong. There is only one way that the wrongly convicted can receive compensation in Scotland: that is on the grounds of 'fresh evidence'. It does not matter, procedurally speaking, whether the accused has been set up by the police, or had poor representation. The years of life spent behind bars won’t be compensated.

But what sort of payment could those who do fit the criteria for a successful compensation claim expect to receive? Between 2016-2020, among the 67 miscarriages of justice formally recognised by the Court, a sum of £376,987.00 was paid out to individuals wrongly convicted in Scotland. This includes interim payments and payments made to individuals who were found to be eligible before 1 January 2016. This information was retrieved by a Freedom of Information (FOI) Response by the Justiciary Office dated 10 August 2021.

We do know that not all of these cases are eligible for compensation, due to the ‘fresh evidence’ stipulation mentioned earlier. However, we can pretend, for argument's sake, that all 67 individuals received an equal share of the total sum paid out: that would be just over 5 and a half thousand pounds (£5,500), for years of their life wrongfully imprisoned. Justice served?

The system is similar but not identical to that in England. If you are fortunate enough to live on English soil, the state is legally entitled to take a percentage of your unlikely compensation to cover your ‘bed and board’ costs whilst wrongly imprisoned.

I was stunned. I had studied law for four years and had no idea about any of this. If I had no clue as a law graduate with first-class honours, what chance would someone with no formal legal education have to ever come across this information?

I aspire to be a Robin Hood-like figure of the legal art world. Taking morsels of legal knowledge from lawyers and dispensing it to the general public in the digestible – and accessible - form of art.

The project: “The System’s Grim”.

This project is still in its early stages, but will eventually become an all-encompassing exploration of the Scots criminal justice system – specifically, its human impact on victims affected by a miscarriage of justice.

The first concept includes painted portraits that will be distorted and warped. The purpose is to introduce viewers to the faces of those innocent people behind the drawings. Each portrait will be accompanied by more work explaining the story of injustice behind each individual. One concept will focus on depicting time lost. COVID has taught all of us that a year can feel like a lifetime, with many people comparing life under lockdown to prison-like conditions. Now, let us imagine 25 years of lockdown. Then, 25 years of actual prison. Finally, 25 years of being in actual prison, for something that you did not do.

25 years is the length of time served behind bars by one innocent person involved in the project: Robert Brown.

Aged 19, Brown was wrongfully convicted for the murder of Annie Walsh in 1977. The interviewing police officers framed Brown by falsifying evidence including testimony. He is one of the minority groups who succeeded in securing compensation for the manifest miscarriage of justice he suffered.

However, because he was convicted in England, he was ordered to pay £100,000 pounds to the State out of his total compensation, for his bed and board. None of the police officers involved has been charged ever since.

Released in 2002, the Court of Appeal took a mere thirteen (13) minutes to decide Brown was innocent.

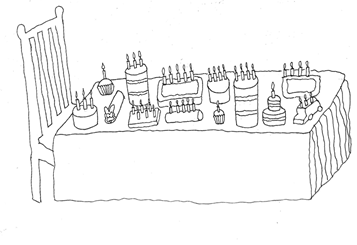

The 25 years he lost behind bars will be represented as an installation of 25 rotting cakes. They represent the 25 ‘lost’ birthdays due to his wrongful conviction. The untouched cake symbolises the good - just out of the wrongfully convicted’s reach. The dripping candles, yet to be blown, show a waiting without purpose. The mould depicts the rotten nature of the system.

A final concept in its early stages is an adult’s storybook. This will illustrate more general information about the CJS (Criminal Justice System), depicting the shocking statistics regarding miscarriages of justice. This will group complex pieces of information into an easy visual format.

Art is how I plan to bridge the gap between the legal system and the lay public it is supposed to serve.

Edward Hopper said: “If I could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint.”

Relegating the stories of miscarriage of justice victims to the mere written medium portrays a diluted narrative of the victims’ experiences. Allowing their voices to be embodied through art is something that will provide more impact, because, at times, things need to be seen and felt too, on top of being read.

Anne Flynn’s work aims to bridge the gap between the criminal justice system and the lay public it is supposed to serve. Graduating in 2019 with a first-class law degree from the University of Strathclyde, Flynn aims to make the law more accessible by removing the need to navigate its linguistic minefield. She has developed a practice of expressive interpretation of case law, statutes and statistics, allowing an examination of the criminal justice system through painting and installation. Flynn is currently studying Fine Art in Glasgow, where her work aims to employ her knowledge of the law to shock and inform her audience.

Annex

LIST OF IMAGES (Copyright © Anne Flynn 2021, with an explicit right of publication and indefinite use given to Human Rights Pulse)

Image 1) Warped sketch of Robert Brown.

Image 2) Sketch of cake installation.

Image 3) Pen-drawing of cake installation.

Image 4) Mould study – materials include: cotton wool and pastels.

Image 5) Mouldy cake painting.

Image 6) Baked Bean illustration. See Docherty v HMA (2016) HCJAC49